About 2 and a half years ago, I set upon what would be the first step of my career in cloud computing. While skeptical at the time, I very quickly adapted and realised the immediate benefits I was getting from AWS, and especially how I, as a developer, was going to benefit.

I first came into contact with cloudformation when our platform team told us about our base infrastructure repo, where I was to spin up the s3 buckets I needed for something I was working on. No problem, I thought, it’s just YAML.

But that’s where it got daunting.

The Rub: Getting Started

At least when I started learning, there really wasn’t a lot to help me get started. I just kind of copy-pasted snippets and asked one of the platform guys to help me lock it down, and that was the way my habits continued for a while.

I started truly understanding how great of an idea Cloudformation and infrastructure as code (IoC) was when I first started studying for some AWS certifications and realised I was no longer going to have to wait for anyone to provision or order anything for me.

While Terraform is starting to pick up steam as of the time of writing, I’m going to focus on CloudFormation, because that’s what I’ve come to know and have a decent handle on. I’ll also be using YAML, because it’s what I’m used to. If you prefer, you can do the exact same things in JSON, just translate the values across and it should work.

General hints

Here’s a few hints for those feeling time poor:

- Use an IDE with a Cloudformation plugin. I use IntelliJ, but VSCode

also has an official plugin and there’s at least a community plugin for vim.

- Make dependencies explicit in your templates. I’ve been caught

out a couple of times where I thought AWS would be smart enough to figure it out, doesn’t always work that way

- If you find yourself bringing up resources with the same general

configuration a lot, use a nested template with parameters instead

- Cloudformation isn’t a replacement for Ansible, Chef, Puppet, etc.

Remember to pick the right tool for the job and don’t just ram Cloudformation in everywhere

- Amazon Connect isn’t supported.

- Remember to use tags and descriptions. It makes it easier to

remember what things are for if someone asks.

- Cloudformation itself is free, you only pay for the resources

you bring up

Infrastructure as Code

The most obvious benefit is version controlled operations. Using git or another VCS to keep track of templates

Templates

It all starts with the idea of a template, and they will all start the same way

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: 2010-09-09This will start you off by telling Cloudformation (herein referred to as CFN) what version of the DSL you want to use. This will be unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

Next we’ll have a look at the different sections that make up a template

Transform

This allows you to use macros to make your templates less verbose.

This is a little beyond the scope of a Getting Started type post,

but the main one I use is the AWS::Serverless transform which

adds some convenience around Lambdas and events

Resource

The main meat of the template, this section defines the infrastructure you’re deploying. You use this section to tell CFN what to provision for you.

For example, say you wanted to define a set of subnets, you could do it thusly:

Subnet1:

Type: AWS::EC2::Subnet

Properties:

CidrBlock: 172.31.0.0/20

VpcId: SomeVpc

Subnet2:

Type: AWS::EC2::Subnet

Properties:

CidrBlock: 172.31.16.0/20

VpcId: SomeVpc

Subnet3:

Type: AWS::EC2::Subnet

Properties:

CidrBlock: 172.31.32.0/20

VpcId: SomeVpcA resource will always have Type and Properties blocks, though

the properties will be different depending on the type of resource.

A full resource type reference can be found

here

Parameters

Inputs to your template. An example might be if you have multiple environments, such as staging and production, and want to put that in resource names somewhere. You can declare them as such

Parameters:

Foo:

Type: String

Description: The foo parameter

AllowedValues:

- bar

- baz

Default: bar

Spam:

# CFN comes with some things to make it a little easier

# to sanity check

Type: AWS::EC2::Subnet::Id

Description: Subnet to connect toYou will always have to declare the type of the parameter. You can find a list of types here

These parameters can be referenced using the !Ref function. For example,

if we had the above parameters, we could use them like such

Foo:

Type: AWS::RDS::DBInstance

Properties:

# ...

DBInstanceIdentifier: !Ref FooMappings

The mappings section lets you define dictionaries that can be

referenced elsewhere in your template. This section can be useful

if you have values which will stay constant across deployments, or

are directly related to a Parameter and don’t require their own

inputs. Use the FindInMap function to grab the values. Example:

Parameters:

Environment:

Type: String

AllowedValues:

- test

- production

Mappings:

InstanceSettings:

InstanceType:

test: t2.micro

prodction: t2.xlarge

Resources:

MyMachine:

Type: AWS::EC2::Instance

Properties:

InstanceType: !FindInMap [InstanceSettings, InstanceType, !Ref Environment]Outputs

Here we can output and export values from our template, for example

DNS names, IPs, ARNs, etc. You can use the GetAtt function to

pull useful values out of resources and put them in the output

Outputs:

Foo:

# A basic output

Value: Bar

DbAddress:

# Using GetAtt

Description: Endpoint address of the database

Value:

Fn::GetAtt:

- Db

- Endpoint.AddressA full template example

Here’s one you can steal and play with

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: 2010-09-09

Parameters:

# When uploading via the console, CFN will let you choose

# these parameters. If using the CLI, use

# --parameter-overrides

EnvironmentName:

Type: String

Description: Name of the environment

AllowedValues:

- test

- production

DeploymentSubnet:

Type: AWS::EC2::Subnet::Id

Description: Subnet to attach to

Mappings:

InstanceSettings:

InstanceType:

test: t2.micro

production: t2.large

Resources:

AppServer:

Type: AWS::EC2::Instance

Description: Our application server

Properties:

InstanceType: !FindInMap [InstanceSettings, InstanceType, !Ref EnvironmentName]

SubnetId: !Ref DeploymentSubnet

# Amazon Linux AMI

ImageId: ami-0b8b10b5bf11f3a22

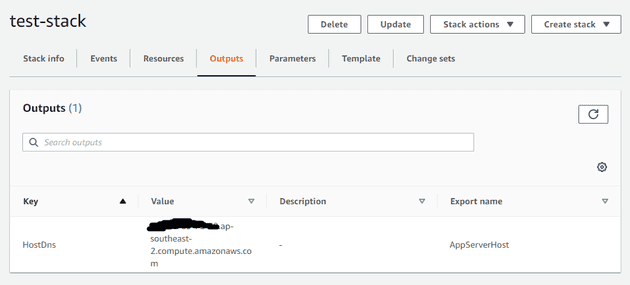

Outputs:

HostDns:

Value:

# Get the public DNS name of the server

Fn::GetAtt:

- AppServer

- PublicDnsName

Export:

# Export it for other templates to use

Name: AppServerHostDeploying a template

Via the console

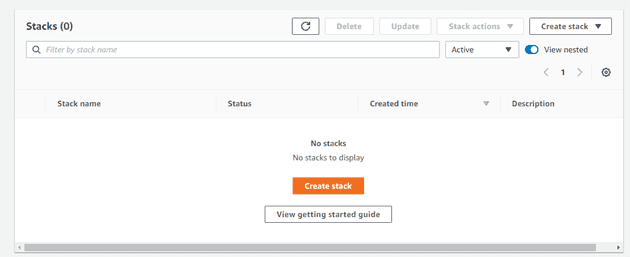

Finally, let’s deploy this bad boy. Navigate to the Cloudformation

console and hit create stack

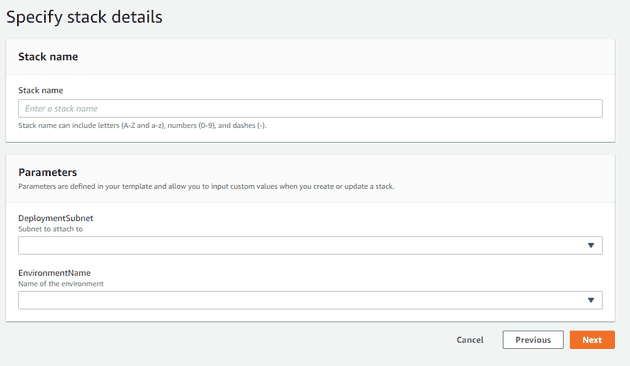

Next we’ll upload the template. You can either manually put it in

S3, or just have the console do it for you. I’ll be choosing

the test environment option and my public subnet from the dropdowns

You can skip the next screen for now, we don’t need it. Just hit

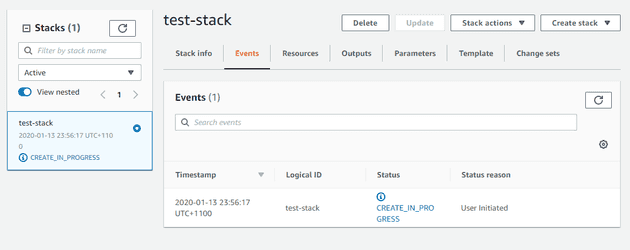

next to go to the review screen and start the deployment.

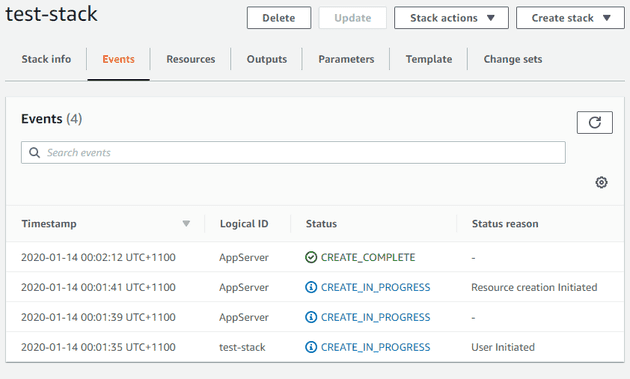

Now sit back and wait until you see AppServer has been created

You can also use this chance to have a look at the outputs

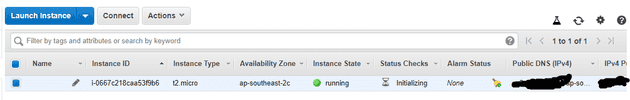

And now navigate over to the EC2 console and have a look at your

instances. You should see your new instance ready to go, and

be able to connect with aws ec2-instance-connect

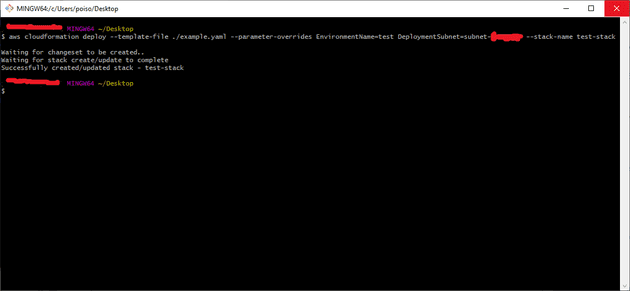

Via the CLI

Here the aws cloudformation deploy command is your friend.

To deploy this one I’ll be running

aws cloudformation deploy

--template-file ./example.yaml

--parameter-overrides EnvironmentName=test DeploymentSubnet=subnet-3e727377

--stack-name test-stackAnd after some waiting we’ll see everything we saw when deploying

from the console, and a message telling us what’s up in the terminal

Useful functions

Finally, we’ll go over some useful functions available in CFN templates, some of which have been previously mentioned

Fn::Refor!Ref- Refer to another value in the template, eg

parameters or resource names, !Ref Foo

Fn::Subor!Sub- Substitute values into a string, eg

!Sub processing-lambda-${EnvironmentName}

Fn::FindInMapor!FindInMap- Look up values in a mapping

dictionary, !FindInMap [Key1, Key2, Key3]

Fn::Join- Join strings together,

Fn::Join:

- /

- - http:/

- !Ref WebsiteHost

- index.htmlFn::GetAtt- Get an attribute from a resource, such as the ARN,

hostname, etc

Fn::GetAtt:

- FooBarServer

- PublicDnsNameConclusion

Just with this you can accomplish 90% of the things

you’ll want to do when you start off. Currently where I work,

all my templates are written similarly to the example one above,

and I have CI/CD scripts using the deploy command and not much

else. Seems to work well enough, though in previous places I’ve

seen stacks just kind of lock up and need to be deleted which worries

me a little. Whether that’s just due to the complexities and

intersections between Jenkins and AWS I’m not sure, but it’s

something I keep thinking about how to solve without nuking all my

infrastructure.